When the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the United States in early 2020, shutdowns and business curtailments hit supermarkets and other food sellers quickly, rippling back through the supply chain to food producers and packaging makers.

For Aaron Anker, who is CEO and owner of small granola company Grandy Organics in Hiram, Maine, it meant a major pivot early in the pandemic away from selling bulk foods to health food stores, including Whole Foods, and to universities, when these buyers closed their bulk granola bins. Bulk foods, which were half of his business, have since recovered, but the experience led the company to broaden its products, including selling smaller packages to retailers and subscription services such as Imperfect Foods, which sells the granola in its food boxes. “When bulk food sales shut temporarily, it forced us to diversify our businesses,” says Anker.

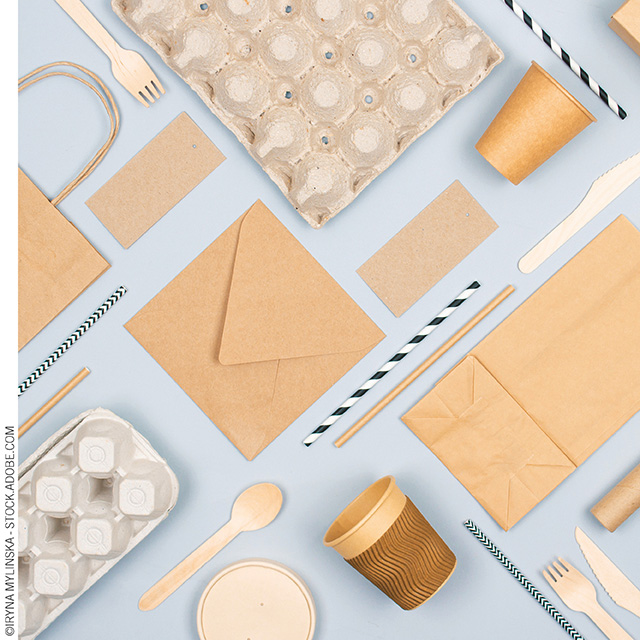

While the bulk business still dominates sales now, Anker continues to sell smaller packages to retailers. He also sells directly to consumers via the Grandy Organics website, and while this part of his business accounts for only a small percentage of his overall sales, it lets him test new packaging such as compostable bags, part of the consumer demand for more sustainable products and packaging that has grown during the pandemic.

Although a small company, Grandy Oats had to take on the challenges the pandemic laid onto larger companies and the food system as a whole. A large shift in demand from consumers, who early in the pandemic were stuck at home and hoarded items, including canned soup and pasta, led to shortages of some products and their packaging. Supply chains were disrupted as manufacturers scrambled to make enough products. Costs rose and international trade issues added to the pressure.

“There was a massive shift from commercial and institutional packaging to retail home use,” says Craig Robinson, global vice president of business development and innovation at PTI, a packaging and inspection company based in Holland, Ohio. “People stopped going to restaurants and large venues [during the pandemic], so the large five-gallon containers of food became unnecessary.” Demand for single-use and takeout containers flourished.

Retail Food Packaging Surges

At the same time, retail packaging surged as more consumers bought their food online instead of at grocery stores and got take-out containers from restaurants. E-commerce accelerated to 17% of grocery sales in the pandemic, compared with 3% of food purchases before it, and it could reach 20% of purchases in the next four years, according to consulting firm McKinsey & Company.

E-commerce changes the demand for packaging, which needs to be stronger, says David Feber, MBA, partner and head of McKinsey & Company’s global packaging practice in Detroit. Amazon has a 17-angle drop test, compared with five angles at retailers, he adds, and some package designs are sustainable to meet consumer demand. One example is detergent in a strong plastic bag within a box that is shipped as is, he says.

Robinson says that early in the pandemic, e-commerce websites such as Amazon Pantry sold flour wrapped in plastic and glass spaghetti bottles double bubble-wrapped and taped. He says a lot of that secondary and tertiary packaging will be replaced by more rugged packaging. “A lot of glass, because of the breakage and weight, doesn’t lend itself well to some of the e-commerce rigors,” he adds.

Efforts are underway to convert some of the heavier packaging to polyethylene terephthalate plastic, but this push is being hampered by the freeze that shut down large parts of Texas in February 2021; some PET resin producers are still not fully back online. This delay has caused resin prices to skyrocket.

ACCESS THE FULL VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE

To view this article and gain unlimited access to premium content on the FQ&S website, register for your FREE account. Build your profile and create a personalized experience today! Sign up is easy!

GET STARTED

Already have an account? LOGIN