Is our food really safe? The plethora of contamination events over the past few years certainly begs the question. The first major contamination event occurred in 1998 when Sara Lee recalled 35 million pounds of various meat products. Recalls were pretty quiet for about eight years, and then:

- In 2006, E. coli was found in packaged spinach that sickened 300 people in 26 states and caused three deaths.

- In 2007, Tyson recalled 40,000 pounds of beef in 12 states due to E. coli contamination.

- In 2008, Topps Meats recalled 21 million pounds of beef due to E. coli contamination; the company closed as a result. Also in 2008, there were recalls of lettuce and spinach due to Salmonella contamination.

- In early 2009, King Nut had a massive recall for Salmonella-contaminated peanuts that sickened 399 people in 42 states.

Over the past three months, several incidents have been reported. Between November 2009 and January 2010, more than 2.8 million pounds of meat products were recalled due to contamination by E. coli or Salmonella. In February, 225 people in 44 states were sickened by Salmonella in imported black pepper that was used to prepare salami and other types of Italian sausage made by a Rhode Island company.

CDC Numbers

In 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stated that 76 million people are infected annually with bacterial contamination, resulting in 325,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths. At that time, the bacteria most responsible for contamination were Campylobacter jejuni, E. coli 0157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, and Cyclospora cayetanensis.

Most authorities contend that there is significant under-reporting, and the statistics have increased dramatically; the only major contamination event reported prior to the CDC report was the Sara Lee incident. Also, almost all recent contamination events can be attributed to E. coli, Salmonella, or Listeria.

Most people believe the growth in the number and magnitude of contamination events can be attributed to several factors, including:

To add to the dilemma, a report recently released by a former U.S. Food and Drug Administration economist indicated that food-related illnesses are estimated to cost the United States $152 billion annually in health- care and other losses.

- the increased globalization of food sources;

- the lack of federal regulations regarding food quality; and

- the desire of food processors to increase revenue and profits, leading them to reduce quality controls that ensure safe food.

To add to the dilemma, a report recently released by a former U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) economist indicated that food-related illnesses are estimated to cost the United States $152 billion annually in healthcare and other losses.

Our government is taking some actions, but they are probably not enough to make a significant difference. President Obama has requested a 30% increase in funding in 2011 for FDA food safety programs. According to the agency, the budget will invest approximately $1.37 billion to strengthen food safety efforts, up $318.3 million from 2010. By contrast, the Food Safety Inspection Service’s budget would receive a less than 2% increase ($18 million) to $1.046 billion, compared to $1.028 billion in 2010.

The increase in contamination events prompts these questions: How can contamination be prevented, and how is testing done today? Researchers are constantly investigating treatment methods that would kill bacteria before the food product is shipped to the consumer, but, so far, none have been successful without adversely affecting the taste or structure of the food product. At present, inspection is the only viable method.

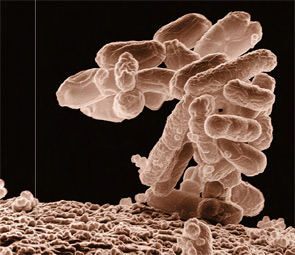

About 80% of testing is done the way most of us learned in high school biology. A meat sample is shipped to a test lab, where a “scraping” is cultured in a petri dish in accordance with established methods. In roughly 24 to 72 hours, any bacteria present in the sample will appear in the petri dish. A trained microbiologist will take a sample, place it on a glass slide, and examine it under a microscope, identifying and determining the number of bacteria present.

ACCESS THE FULL VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE

To view this article and gain unlimited access to premium content on the FQ&S website, register for your FREE account. Build your profile and create a personalized experience today! Sign up is easy!

GET STARTED

Already have an account? LOGIN